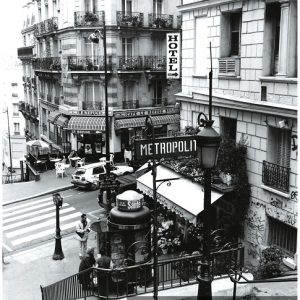

Toby Ray Vandenack is an American photographer best known for his black and white images of New York and Paris. Born in Wisconsin in 1958, he became involved in photography at the age of sixteen making photographs for the school newspaper and yearbook while attending high school in Green Bay during the 1970s: “I was sixteen when I developed my first black and white photographs in the darkroom during my high school days in the 1970s—a magical experience that turned into a lifelong passion.” Vandenack’s work has since been widely published and is included in collections throughout the world. He has received numerous awards for his photography, including master print competition from the Professional Photographers of America. “Intensity of vision” are among words used to describe Vandenack’s photographic style in a Retrospective Exhibit statement by Susan Talbot Stanaway, Art Historian and Curator of Art: “Vandenack presents fresh, evocative, and tactile views that are, as well, beautifully crafted.”

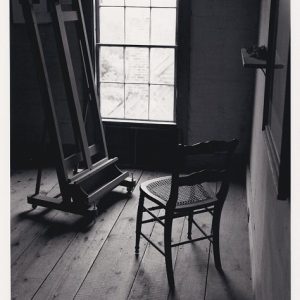

In a digital world Vandenack embraces technological advances in photography, yet remains committed to his traditional black and white film roots: “Digital imaging and tools like Photoshop are amazing, but to me, there’s something therapeutic about bringing life back to a negative by printing and developing it in the darkroom,” Vandenack remarks. “I had printed some 1880’s vintage glass plate negatives for a museum a few years back. As I watched those images appear in the developer tray, it felt as though my darkroom had transformed into a Time Machine; developing prints still evoked a magical feeling, even after all these years!” Toby Vandenack is recognized as a master printer still practicing, and occasionally teaching, the gelatin silver photographic process today:

HISTORY OF BLACK & WHITE PHOTOGRAPHY: Most twentieth-century black-and-white photographs are gelatin silver prints, in which the image consists of silver metal particles suspended in a gelatin layer. Gelatin silver papers are commercially manufactured by applying an emulsion of light-sensitive silver salts in gelatin to a sheet of paper coated with a layer of baryta, a white pigment mixed with gelatin. The sensitized paper is exposed to light through a negative and then developed out—that is, made visible in a chemical reducing solution. William Henry Fox Talbot introduced the basic chemical process in 1839, but the more complex gelatin silver process did not become the most common method of printing black-and-white photographs until the late 1910s. Because the silver image is suspended in a gelatin emulsion that rests on a pigment-coated paper, gelatin silver prints can be sharply defined and highly detailed in comparison to platinum or palladium prints, in which the image is absorbed directly into the fibers of the paper.

–National Gallery of Art

Photography and the Spirit of Rock and Roll – Not Fade Away

A friend sent this photo of my alter ego “Toby Ray Van” playing for a fundraiser at the Riverside Ballroom in Green Bay (2014). The historic Riverside was one of the last venues for the fateful Winter Dance Party Tour. That event played when I was just an infant, February 1, 1959, two days before the plane crash in which Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and The Big Bopper perished near Clear Lake, Iowa; forever remembered as The Day The Music Died. Hopelessly nostalgic, I felt a special vibe playing on the same stage that Buddy Holly had played, over fifty-years after his death.

I never gave it much thought in my younger days, but I’m now grateful to have had both photography and music in my life since I was a teenager. I’m not exactly sure what one has to do with the other, but I do know, they both come from the soul and have influenced the way I see this world through the lens of a camera;

Not Fade Away…